The Fallout of Great Expectations

The Atlantic article that ran in June, “We’re learning the wrong lessons from the World’s Happiest Countries” begins:

“Since 2012, most of the humans on Earth have been given a nearly annual reminder that there are entire nations of people who are measurably happier than they are. This uplifting yearly notification is known as the World Happiness Report.”

Northern European countries have swept the top performing countries for happiness since the inception of the report. The writer of the article points out that the word “Happiness” in the report title is a bit misleading—that the report is really more a metric of contentment. This may feel like splitting hairs, but the point is this is not a report on exuberance or lives filled with more exclamation points—this is a report about people’s perception of of how well life is going for them.

Predictably, the happier countries have a more comfortable standard of living, with the highest ranking countries also having services like “universal health care, ample paid vacation time, and affordable child care.” Intuitively if you are stressed about meeting your basic needs--which is true in countries that have been impoverished by our global inequities and is true for the large segments of rich countries where there are massive divides between the haves and have-nots--happiness is harder to come by.

But there is another element to happiness (or contentment) identified in this report that goes beyond stable and reliable capacity to meet basic needs: expectations.

The article quotes Jukka Savolainen, a Finnish American sociology professor who adds insight into why Finland continues to rank so highly on this annual Happiness Report. He introduces the concept of :

“LAGOM, a Swedish and Norwegian word meaning ‘just the right amount… The Nordic countries are united in their embrace of curbed aspirations for the best possible life.”

Once you get beyond meeting basic needs, the recipe for happiness, it seems, is expecting less. This isn’t a terribly wild idea, but it does go against the mythos and ethos of the United States, where the credo of the day is best captured in the old Burger King jingle “Have it Your Way! Have it Your Way!”

The US clearly fits the mold of a wealthy country where there are vast inequities. There are many people in this country whose basic needs are not even close to being met. But there are also swaths of wealthy people in this country who have every basic need more than met who are not terribly happy or content. And for that segment of the population, the expectation cure is relevant.

As a person who has lived a life with a lot of privilege, who grew up basting in the “Have it Your Way” mythos of the United States, I’ve needed a lot of re-training around expectations. And, as luck would have it, life usually does a good job of delivering those lessons.

While I consider myself to be a reasonably competent person, I also know that I’m a slow learner in certain realms. I have to touch the proverbial hot stove several dozen times before important psychological lessons really sink in. And the lesson of the gift of curbed expectations has absolutely been a slow awakening for me, and one which I can easily lose sight of for a time and have to find my way back to.

As is so often the case for me, when I land on anything that feels wise and true, it seems its origins can be found in Buddhist philosophy. In this instance, the Buddhist concept of non-attachment is relevant. Buddhist correctly point out that suffering is an inevitable part of life (all lives, might I add…even the privileged ones), and it identifies one of the etiologies of this suffering as being attachment to outcomes over which you ultimately don’t have control. In essence: the trap of wishing for things to be different than they are. The weather is a classic example of this…the fervent wish of my February self to be able to wear flip flops and a tee shirt, and the fervent wish of my August self for a break from unrelenting sunshine and heat. Wishes that are outside of my control, capricious, and ultimately damage contentment because they are unreachable.

In the year of the pandemic our wishes shifted. The things that pre-pandemic felt like givens became precious and rare—things to be pined for. In early summer many of those things became available again, and with that shift, our (or at least my) wishes shifted. This past June I spent a week with family for the first time in a long time. The gathering would have been unthinkable in June of 2020. It was a wonderful week. But the weather… terrible. Rainy and cold, not at all what we wished for a beach trip. And so while the lessons of the pandemic hadn’t completely faded and the thrill of being able to see loved ones again was real, the expectations for “how it should be” were creeping up again. The happiness bench mark forever receding into the distance.

As the Delta variant and breakthrough cases have become more prevalent and daunting in this country in recent weeks there is a kind of wishing whiplash. What was possible in June, feels less possible now, but the wishbone is sometimes delayed in titrating to reality.

And so in the whiplash, I find myself paradoxically wishing for lagom. Wishing I wished for less. Wishing to have a touch more of the Nordic philosophy at my fingertips, instead of having to dig for it.

Between the pandemic and climate change the “givens” of my childhood are simply, no longer givens. What we can expect from the world, from other humans, from life—feels fairly hazy. I imagine we will all continue to make plans, but probably will experience far more of plans falling through than used to happen from fast shifting circumstance—fire spreading, hurricanes barreling down, variants ticking up.

And if we can learn to expect less, perhaps we can get a little closer to contentment anyways.

One Year In

Here we are one year in from the date the World Health Organization officially declared the pandemic. I had a few more frantic days after the declaration in the office before it shut down as well, and Zoom life began in earnest. With the ramp up of vaccines there is a feeling of light at the end of the tunnel. Only the side-by-side articles that report on vaccinations remind that variants are rampant and that the vaccine rollout exclusively in wealthy nations is not a global solution to a global problem. That said, I’m trying to not allow the more morose thoughts overshadow the strand of light pulling me out of the longest winter I’ve ever experienced.

Temperatures in Cambridge tipped into the 60s today, and I felt like weeping with relief. I have never loved winter, but this year I’ve felt immobilized by it. Because this year the snow and freezing temperatures spelled the end to the limited socializing that was available in warmer months. In the spring, summer, and fall, my husband and met up in parks with friends for social distanced gatherings regularly. We stretched this all the way into December—meeting up for an outdoor meal with a friend with our sleeping bags, warmest down coats, and layers of clothes and hot water bottles at the ready. But when winter set in in earnest, with snow and ice coating the ground and bone deep wind chill, it felt there was really nothing left to do but hunker down. So hunker we did.

At some point in the last month I needed to find a specific date on my 2019 calendar. As I scrolled back through the months of my pre-pandemic life, I had the sensation of reading my childhood diaries: a life both familiar and quite foreign all at the same time. I used to have the problem of doing too much—overcommitting—or so I was told. Only, I’m not sure now it was a problem, maybe it was just the way I am. Maybe it fed me.

I took a bread making class once and the instructor showed us how to knead the dough until the gluten knit together so that when you stretched the dough it would become so thin you could see through it, but it wouldn’t break—a kind of culinary stained glass. The Goldilocks rule applies here—you don’t want to work the dough too much or too little—just the right amount. And in this most recent season of the pandemic, I can safely say, as an extrovert, there have been far too few inputs, and I feel like a withered version of myself. Stretched thin, but not by things I love, rather by a dearth of things I love.

We are all hitting on our particular one-year marks of the pandemic. The first cancelled trip or event. The last day of in-person-classes or going into the office. The first day of having to go into work and feeling like doing so was putting your life into peril. The first death of a loved one. The story lines are all different. And how we’ve moved through this year is varied. Some have chosen to stuff cotton in their ears and ignore guidance from the CDC—others have held themselves to strictest standards. And most of us fall somewhere in-between.

My losses have been nominal in the grand scheme of losses. But they are none-the-less painful: I miss seeing loved ones in person.

I built much of my life and career around assiduously avoiding a screen-based existence. I was a teacher before I was a therapist—and when the school where I taught developed a 1:1 student to i-Pad ratio, I had a true conniption and fired off missives to the administration about how it would be so detrimental to have students constantly engaged in their screens rather than with each other. I was a lone voice of dissent, and the program rolled out. I eventually left the school, and went to one of the rare school programs where students turn over their devices for the entire semester—and live a truly unplugged existence. A similar thing happened after a summer where I worked taking teens on a trip in Costa Rica. As their trip leader, I had to carry a cell phone that their parents had access too. After endless calls with parents who in the end seemed rather ill equipped to let their child out of their grasp, I vowed I’d find a summer job where cell signal couldn’t find me. And for the next seven years I worked summers leading backpacking trips for the National Outdoor Leadership School in the remote Wyoming Rockies, where cell signal was blessedly absent, and students were notably more content.

In any case, more than most of my peers, I’ve made life choices that have often been explicitly guided by keeping technology at bay. Of course, I’ve given in in a thousand ways my early 20s self would cringe at. And the concessions haven’t unilaterally made life worse, as I feared when I had my student i-Pad conniption back in my teaching days. I have a website and a smartphone, and now, of course, over the last 365 days, my entire work life, and much of my social life has moved from three dimensions into two dimensions. And I am genuinely grateful for it. I’m so grateful I’ve been able to keep working and seeing clients over video over this year—and that this medium has allowed for genuine connection. I’m so grateful for the Face-timing with friends and family. Grateful and resentful. All in one bite.

Mostly I’m on my knees grateful for the promise of spring in New England. Even if the world could end in a thousand horrible ways. Even if the variants are out there swirling. Even if, even if… the sunshine today feels like redemption after a long, long year, and the first buds on my neighbor’s tree feel like the gold medal for making it through winter.

The Phrase of the Year

In 2006 I did a brief homestay in Cairo. My host family spoke English quite well, but all conversations were sprinkled with the Arabic phrase, “Inshallah”—meaning “Godwilling.” This phrase was applied to distant, big plans, and to the smaller daily plans, like when we might have tea.

It was the constant reminder that all of our plans hang on gossamer threads that can be severed in an instant.

There is so much truth to the phrase “out of sight, out of mind.” Humans have an enormous capacity to turn a blind eye. This is no doubt individually protective, if often detrimental (both individually and collectively). Different cultures have different ways of bringing awareness to the ephemerality of the human experience. Some highlight that death is coming that the world is uncertain—others try to keep these realities far enough away that they can be mostly ignored. The culture I live in in the United States is the latter—an ostrich culture.

Only 2020 was relentless in ensuring that I remove my head from the sand over and over again. The blaring messages of 2020: Death is always close at hand. You have no idea what tomorrow will bring. There are undeniable injustices taking place every single day. You are complicit in these, whether you want to be or not.

And as hardwired as I am by the cultural waters I’ve swum in forever to plunge my head back into the sand—2020 has done some rewiring.

While it is undoubtedly inappropriate for me to co-opt the term Inshallah, it has nevertheless become an unspoken hum in my head. “I’ll see you for a walk tomorrow” (Inshallah). “I’ll be teaching on Tuesdays this semester” (Inshallah). When we can travel again, we’ll go…” (Inshallah). And on and on.

Because there is something that feels both hefty and light in this phrase. The heft: Perhaps I won’t go on that walk tomorrow because I’ll be dead by then. The light: that this is common—this is a fate we all share—this is what it is to be human, with a dose of gallows humor—which is a tonic in the dark times. And there is real humility in this phrase. Humility that none of us are soothsayers. None of us can say with irrefutable certainty that THIS is how it will be. A truth highlighted by events of this week. Poetry, as is often the case, says it best—

…

David Whyte’s “The House of Belonging”

I awoke

this morning

in the gold light

turning this way

and that

thinking for

a moment

it was one

day

like any other.

But

the veil had gone

from my

darkened heart

and

I thought

it must have been the quiet

candlelight

that filled my room,

it must have been

the first

easy rhythm

with which I breathed

myself to sleep,

it must have been

the prayer I said

speaking to the otherness

of the night.

And

I thought

this is the good day

you could

meet your love,

this is the gray day

someone close

to you could die.

This is the day

you realize

how easily the thread

is broken

between this world

and the next

and I found myself

sitting up

in the quiet pathway

of light,

the tawny

close grained cedar

burning round

me like fire

and all the angels of this housely

heaven ascending

through the first

roof of light

the sun has made.

This is the bright home

in which I live,

this is where

I ask

my friends

to come,

this is where I want

to love all the things

it has taken me so long

to learn to love.

This is the temple

of my adult aloneness

and I belong

to that aloneness

as I belong to my life.

There is no house

like the house of belonging.

…

Each time I read this poem a different line grabs me and pulls me in. Today it is: “this is where I want/ to love all the things/ it has taken me so long/ to learn to love.” Because remembering that each moment we are living, we are also dying is really, at the core, about loving. Loving with more tenderness or ferocity all that we will eventually lose, which if you really pause to consider will break and fill your heart all at once.

Examining Fragility

As a counterpoint to Eleanor Porter’s Pollyanna published in 1912, which I wrote about earlier this week, there is Margery William’s The Velveteen Rabbit, published in 1922. In the decade between the publication of these two popular children’s books, World War I happened. It’s not hard to imagine that the tenor of the world in the intervening years between the two books influenced the core message of The Velveteen Rabbit—also known as “How Toys Become Real.”

The most famous passage takes place in the nursery—a conversation between two toys: the title character and the skin horse:

…

“What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

“Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,” he asked, “or bit by bit?”

““It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.

…

“It doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept.” This line has been humming in my mind in recent weeks as I’ve spent more time examining my white fragility, which is defined as: “A state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves.”

Fragile is not a word I’ve previously identified with. In my self concept I am strong, not fragile. I can run marathons and carry large backpacks over high mountains. But this isn’t about physicality. This is about the inner landscape of my human experience. And looking here I am starting to see my own fragility.

Across the board, on all topics, I am averse to criticism. I feel intense shame if I am “called out” for something I’ve done that is hurtful. A word I do identify with is: sensitivity. I am a feeler. Of all the feelings. On very high volume and saturation. But as the discussion on racism continues, and I keep trying to look a little deeper, there is a distinction between fragility and sensitivity. Not all white people may identify as sensitive, but white Americans who have been soaking in the bath of white privilege for centuries, and who haven’t done any unpacking of their white experience likely have white fragility. My aversion to getting feedback that I need to hear is a fragility problem, not a sensitivity problem, ultimately.

In her LongReads article, “Whiteness on the Couch,” clinical psychologist Natasha Stovall, “looks at the vast spectrum of white people problems, and why we never talk about them in therapy.”

Sometimes you read or hear something that pins you to the wall. This sentence was one of those for me:

“Yet the field of psychology, so intimately involved in all matters of the white heart, is nowhere to be found. Despite the outsize drama that whiteness brings to the public scene, it is still not much more than a cognitive wisp in most white Americans’ daily brainscape, including those of most, but not all, white therapists.”

Also from the article:

“In the 1960s, a group of black psychiatrists petitioned the American Psychiatric Association to add “extreme bigotry” to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, citing the frenzied, often homicidal violence against civil rights activists. The APA rejected the petition, making the claim that “extreme” prejudice was so normative among American whites that it was more of a cultural phenomenon than an individual pathology. (An interesting piece of intellectual jiujitsu — who makes up a culture if not individuals?) Harvard professor and psychiatrist Alvin Poussaint has suggested that more intense strains of racist belief should be classified as a psychosis, specifically a subtype of Delusional Disorder. He described his patients who “projected their own unacceptable behavior and fears onto ethnic minorities, scapegoating them for society’s problems.” Poussaint interpreted this scapegoating as a symptom of deeper psychological dysfunction that presents a danger to the patient and those around them. He found psychotherapy to be an effective treatment: “When these patients became more aware of their own problems, they grew less paranoid — and less prejudiced.” Poussaint has called for guidelines to help mental health providers recognize “delusional racism.” Otherwise, Poussant warned, “delusional racists will continue to fall through the cracks of the mental health system, and we can expect more of them to explode.”

The connection between fragility and privilege is clear. The world, ultimately is a scary place for “people who have to be carefully kept.” And for those who have had the privilege of being “carefully kept” by a society that has institutionally favored their identity, there is intense fear about loss of privilege and giving up the “goodies.” (And of course the world is even scarier for those who have not been privileged, and whose fears come to pass with regularity). But there are no guarantees and there is no ultimate security blanket in life, even if you have the resources to build a fortress with high walls and a big moat. Each human life will include suffering. Ultimately, it is better to become less fragile and more real, to be able to survive the vicissitudes of the human experience no matter who you are.

There is so much fear from white people around giving up privilege. Fear even from white people, who care about social justice. But Stovall’s article asks white people to consider in fact what gains there might be from giving up privilege.

Stovall writes:

“Therapists rarely think to question the role of racial identity in their white patient’s lives, but Benjamin Franklin noted white people problems back during the wars between indigenous tribes and settler Europeans. He puzzled that freed prisoners of war, Native and European, generally chose indigenous life over settler ‘civilization.’ He diagnosed a problem in European culture, in whiteness: ‘With us are infinite Artificial wants,’ he wrote.”

“With us are infinite Artificial wants.” (capitalization his)

I had a friend say to me a short time ago that I am generally circling around the same question in my blog: my desire to live all the lives, my “grass is always greener” pathology. And it’s true. And as I’ve noted, it is a terribly privledged lament. I’ve started to wonder if I can trace the origin of this difficulty of staying content, in what is actually an incredibly good life, back to an excess in privilege. And here, the memorable lyrics to “Food, glorious food,” a song in the musical Oliver, sung by the workhouse boys: “Rich gentlemen have it boys, indigestion…”

To be clear, not all white people experience the same level of privilege—not even close. Economic disparity, and your own individual constellation of privileged or disparaged identities (including race and sexual orientation and body size and physical capacity and mental acuity and relationship status and religious orientation…on and on). All of those flavors of privilege and disadvantage are important to examine. But for today, I am spending time with white privilege and the attending white fragility.

And I am finding myself wanting to become more real. More resilient. Less fragile. Less prone to indigestion and to the cognitive dissonance that arises from wanting to be good, and knowing that in some particular, and significant ways, I am not. And knowing that this work can be of benefit to the world, and to my own life.

The question that necessarily follows is HOW?

Here Stovall quotes, psychoanalyst Melanie Suchet: “The dismantling of white authority is not a smooth process. There is no linear absolution, (for whites) the colonizer within can never be shed, only disrupted again and again.”

Stovall quips, “like any therapeutic process, the healing of whiteness involves significant ‘discomfort,’ — mental health’s favorite euphemism for emotional agony.” And she suggests mindfulness as part of the path. A way of attuning to the habits of our mind, of pausing long enough, to not walk down the same road again. And perhaps a twelve step programs of sorts focused on whiteness, where white people can muddle their way through without adding more emotional labor to the BIPOC community. And stopping the racist behaviors—first, and foremost—even if it remains a life’s continual work to develop new channels in minds and hearts.

Pollyanna

My inner realist has always snarled when it has caught a whiff of a pollyanna. Until this weekend, when I was in Littleton, NH and came across this statue of Pollyanna, I’d never actually explored the origin of the term pollyanna—“an excessively cheerful or optimistic person,”—I just knew I prefer to give pollyannas a wide berth.

But when I came across this statue, I got curious about the literary character for whom this term is named, and I read more about the original 1913 novel, Pollyanna, by Eleanor H. Porter, whose title character, enshrined above, in the author’s home town, was a girl who played the “glad game”—always looking for the good in any situation, no matter how bad it might be. And based on the plot synopsis, I’d say, it was fairly bad for Pollyanna. She was orphaned and had to go live with her dour aunt who disliked children in a town full of misanthropes. But as the story goes, she won them over, helping them to see good, no matter what. In one anecdote Pollyanna, finds that all that is left in the Christmas gift bucket is a set of crutches, but instead of feeling sorry for herself that she won’t have a Christmas gift this year, she feels glad that she doesn’t need crutches.

Does she sound insufferable or what?

Of course you could argue that she is incredibly well adjusted and resilient and adaptable, and no doubt if such a human existed, she would be. But I find the part about her winning over the dour aunt and misanthropic townspeople to be, exactly what Pollyanna originally was: a tale.

I’m thinking of Brené Brown’s explanation of sympathy vs. empathy now, which is captured so well in this two minute video:

“Empathy is feeling with people...Rarely if ever does an empathic response begin with ‘at least.’

I love Brown’s use of “silver lining-ing”as a verb. She points to this behavior as a telltale sign that someone is in sympathy (which drives disconnection) vs. empathy (which is connective). It seems to me that Pollyanna is an artist with one brush stroke: the silver lining. The “glad game.” Looking for the good in any situation, which is far too tone deaf for the real human experience.

And YET, Pollyanna was a bestseller. So popular that it turned into a long series, and as recently as 2008 there was a “Glad Club” formed in Denver, Colorado, based on the ideology of this fictionalized character.

Here’s where the plot got really juicy for me: Pollyanna gets hit by a car, and she overhears the doctor saying she might never walk again, and even she cannot continue playing the glad game, UNTIL, miraculously, she is healed, and she is able to squeeze out another silver lining: now, more than ever, she is extra appreciative of her legs. This left me wondering how it would have gone for her had that tidy plot development of a miracle cure not occurred. Would Pollyanna have had to expand her tool kit from the “glad game” (which I think could also be called the silver lining club) and learn some other skills?

Do I seem overly frustrated with a fictionalized character? Yes. If you are reading frustration, you are right. Snarl truly is the best word I can describe for what happens to me internally when in the real world I feel I am in the presence of a pollyanna.

The truth is—being able to be positive is an incredibly useful skill. Especially if you can muster that in a time of duress. It’s a skill I could absolutely work on. But there is something about a pollyanna-ish response (and the field of positive psychology even) that feels more like a dagger than a balm if that is the sum total of the response you get to a painful experience.

There are some new flavors of struggle on the menu for each of us this year. There is a lot of suffering. For that reason I have been revisiting The Empathy Tool Box—a post from several years ago.

In the closing to that post I write:

“The antidote to the ‘emotional, spiritual and psychological violence’ caused by a phrase like: ‘everything happens for a reason’ is the truth, kindness, and wisdom in this lifeline of a phrase, from writer, Tim Lawrence:

“Some things in life cannot be fixed. They can only be carried.

Some things in life cannot be fixed. They can only be carried. Some things in life cannot be fixed. They can only be carried. Say it, sing it, write it--this is the mantra of Empathy. There is no return to a magical land of "before" or "normal" when something terrible happens. Perhaps, with time, your world grows large enough to hold your grief and joy side by side, but the grief never vanishes.”

…

Being a pollyanna is something, it seems to me, that is best done in private—like flossing your teeth or trimming your toenails. It is good for you—even great for you—to privately examine how you can make the best out of a hard time and how you can find gratitude in the dark. But trying to urge another struggling person towards this place—it seems to me—is usually about your own discomfort with that person’s discomfort, and not about offering solace during a challenging time.

An American Tale

My dog has always had a vendetta against appendages on her plush toys. At six pounds, it takes her a while to chew through fabric to remove the offending parts, but this week, she finally, chewed through her rat’s tail, a project she’d been working on for months.

I feel like I’ve been doing my own chewing through some American tales for the last couple of months. The last time I wrote a post was on cusp of Memorial Day weekend, when I was awash in my familiar pattern of lusting after things that are unavailable to me—namely in this moment—the freedom of movement that was available before Coronavirus was a household word.

In hindsight, this was a tone-deaf post, given what was happening in the country as I wrote, unaware of the news unfolding (I’m guilty of often being behind the times). By Memorial Day weekend, George Floyd’s name was gaining global recognition, and the spotlight was landing on the lack of freedom and security (among many other things) that black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) have experienced in this country, since this particular expanse of geography was conceived of as a country.

As far as we know, humans are the only story telling animals. In Jonathan Gottschall’s book, The Story Telling Animal, he writes:

“We are, as a species, addicted to story. Even when the body goes to sleep, the mind stays up all night, telling itself stories…Story is for human as water is for a fish—all-encompassing and not quite palpable.

Not quite palpable. So, how do we begin to understand the water we swim in? The stories we’ve bathed in since before we were born.

In so many ways, on a larger scale than has happened before in my lifetime, as a white person, I’m being given the opportunity to really look at the myths that I’ve learned and lived and upheld throughout my life in ways that are a mixture of conscious and unconscious.

If you’ve read this blog for any length of time, you’ll know that my life is saturated in privilege. Privilege of all kinds. Every identity I carry, except for being a woman, is an identity that is privileged by the society I live in. This privilege has not saved me from suffering. No human life is exempt from suffering. But it is suffering that has been private and personal, not systemic.

The invitation is on the table now for white people to stop burying their heads in the sand. Maybe especially white people like me who profess to care about social justice—that we, not just spout narrative—but actually examine our own complicity and our own complacency in racism and in deep injustice.

I don’t know what this is in reference to, but in my notes from a lecture in my yoga teacher training, I have underlined, “We try to blame others, but it’s always you,” which feels appropriate to this moment for my life. How instead of pointing a finger out, can I turn the gaze inward? And how can I do this in a way that isn’t shaming, but is willing to see where I’ve been wrong and done wrong?

As my fiancé and I get ready for our wedding, we’ve been spending a lot of time with Alain de Botton’s novel/philosophical musings, The Course of Love.

In the section of the novel titled “Beyond Romanticism,” Alain de Botton writes:

“Pronouncing a lover ‘perfect’ can only be a sign that we have failed to understand them. We can claim to have begun to know someone only when they have substantially disappointed us. However, the problems aren’t theirs alone. Whomever we could meet would be radically imperfect: the stranger on the train, the old school acquaintance, the new friend online…Each of these, too, would be guaranteed to let us down. The facts of life have deformed all of our natures. No one among us has come through unscathed. We were all (necessarily) less than ideally parented: we fight rather than explain, we nag rather than teach, we fret instead of analyzing our worries, we lie and scatter blame where it doesn’t belong. The chance of a perfect human emerging from the perilous gauntlet are nonexistent.

What does this have to do with racism and taking real look at my white privilege and fragility? This, for me is how the threads connect: Taking feedback is exceedingly hard. Being willing to look and see how I am imperfect and how I cause pain is exceedingly hard.

The people who we live with most closely are the ones who most reliably hold up the mirror and allow us to see how we are fallen creatures. And this is not an act of cruelty (well…sometimes in the heat of an argument it might be). But when done with love, this form of feedback is an expression of love. It is also an expression of faith—that we needn’t remain as we’ve been. That we can become. And that we will always be in process. We never arrive.

There is an urgent invitation for white people to become. To shed American tales—the myth of meritocracy of colorblindness—to wake up.

White people are being given feedback. Can we take it in? Can we metabolize it? Can we be changed by it? Not to become perfect, but to become humble. To be willing to see things as they are, rather than as we’ve believed them to be, or wished for them to be. To be willing to unlearn, and to be open to new learning and new action.

FOMO, JOMO, and YOLO

Since the pandemic began, I’ve heard from various people that they are no longer mired in what modern parlance calls FOMO: Fear of Missing Out, or what Søren Kierkegaard more elegantly called, “the despair of too much possibility.” Clearly it is easier to not be mired in wistfulness or jealousy about what is happening out there, when in fact, nothing, is happening out there. But these people aren’t just noticing the absence of FOMO in their lives, they are simultaneously noticing the arrival of JOMO: Joy of Missing Out.

My friend who had a social engagement every night pre-pandemic, is actually reveling in watching TV on her couch. My friend who went out of town every weekend, is truly enjoying slow walks around the neighborhood instead. People, myself included, who used to lead busy, “keeping up with the Jones’s kinds of lives,” are in fact noticing some real benefits to a quieter, slower pace.

If you’ve read my blog for any length of time, you’ll know that a core theme that I struggle with in my own life is: paradox of choice. I want this, that, and I’d like the other too. It is a wildly privileged lament, and an obnoxious one at that given the backdrop of a pandemic, but none of those facts make it go away. Given that I am only one person, I cannot have this, that and the other. And being human with a very human mind, I often convince myself that the thing I am not doing is THE thing I should be doing, and if only I’d done that thing then my life would be just right. This is the beginning of my personal yellow brick road into one of my most frequented rabbit holes. It’s not so much fear of missing out on a particular event, but rather a fear of missing out on another life--a ghost life—that I could imagine leading.

But this particular (malignant) thought pattern has been blessedly silenced as the world has slowed this spring. With no options to gnaw on, the beast of FOMO is subdued. Along with friends who have similarly felt a silencing of this part of them in the wake of the stay-at-home orders, we’ve wondered, will it last? Will we continue to breathe life into JOMO—into the smaller, quieter, close at hand joys.

I fear, for me, it will not last. Because even though the city I live in is very much still staying at home, much of the rest of the country and globe is not. People are headed to the beach and to the mountains and over to see friends. Sanctioned, or not, people are out and about again. And so my particular beast of FOMO is rising again from hibernation, and a very fetal JOMO is quickly losing pace.

At its root, FOMO is about comparison. Comparison is a dirty habit, but one that we humans, as social animals, all engage in. In Alain de Botton’s book, Status Anxiety, he points out:

“Modern populations have shown a remarkable capacity to feel that neither who they are nor what they have is quite enough.

He goes on to say:

“Status Anxiety is the feeling that we might, under different circumstances, be something other than what we are—a feeling inspired by exposure to the superior achievements of those whom we take to be our equals—that generates anxiety and resentment.

Status anxiety and schadenfreude (the German term for delight in someone else’s misfortune) go hand in hand. And together, they are part of the underbelly of FOMO. Of course, you might just be really be sad about missing out on an event or experience—but often the sadness of missing out on the event is accompanied (even eclipsed) by the worry about what the missing out means about you.

YOLO—You Only Live Once, is another popular acronym, that has been adopted as a rallying cry for “just doing it” (whatever it is), and as a pardon for “just doing it” (no matter how destructive it is). For those of us afflicted with unhealthy doses of both FOMO and YOLO, the fallout is constantly feeling like you aren’t doing enough, not today, and not with your life in general.

Alain de Botton diagnoses this ill in this way:

“The price we have paid for expecting to be so much more than our ancestors is a perpetual anxiety that we are far from being all we might be.

Our expectations about what life might be like, are crippling. I realize this isn’t true for everyone. Some people have well developed JOMO, and aren’t inflicted with so many FOMO and YOLO tendencies. This post is not for you. This post is for those of you, like me, who suffer from ridiculous expectations about what a Thursday night should look like—about what a life should look like. This post is for those of you who have felt some relief in the pandemic reducing your expectations—in feeling “let off the hook” of who you are supposed to be and what you are supposed to be doing as a side effect to the human race being brought to it’s knees by a virus.

I want to hold on to what I learned when the world got quiet. Because outside my door, things are growing louder by the day, and I know how hard it is to bring lessons from another time into the present. Even though from a public health prospective the world should still be quiet, it isn’t. People are going out and doing different things. They are taking pictures, and sharing them. And I will look at some of them, and I will feel FOMO and YOLO rising like bile in my throat. And I hope (pray really—to what I’m not sure) that I will be able to summons JOMO—to remember that in fact, I can be happy in a quieter life.

In April I sat out under the tree in my backyard that was full of blossoms and I drank a cup of tea, and I felt deeply content. I felt lucky. I felt happy.

The blossoms are off now, replaced by bright green leaves. The warm breeze is just right tonight. And the bowl of ice cream next to me is delicious. It is a night for feeling content. Lucky. Happy.

Nothing, and everything, has changed in a month.

As is perennially true for me, it is my mind, not my life, that needs help. May JOMO survive as the world grows louder. May JOMO grow and grow.

On Risk

Of all the news articles I’ve consumed over recent months, this one from The New York Times: “How Pandemics End” has, for obvious reasons, grabbed me the most. Because, quarantine fatigue is real, and while not nearly as serious as the pandemic, quarantine fatigue is weighty, as the ambiguous future stretches on and on.

The article identifies two ways pandemics end:

“According to historians, pandemics typically have two types of endings: the medical, which occurs when the incidence and death rates plummet, and the social, when the epidemic of fear about the disease wanes.

I am interested in both of these options: hopeful for the first, and curious about the second. Buddhist mindfulness traditions have long known that the mind bends reality more effectively than any other tool available to humankind. If the medical end to the pandemic does not come, when will the scales collectively tip towards less fear about the disease than the impact of avoiding the disease?

In another lifetime (read: 2019) I was a part-time backpacking instructor. “Risk Management” is a large part of the curriculum you teach students who you are training to be competent in the backcountry. Management is a key term here. In the wilderness, there is no such thing as “Risk Avoidance,” (nor is there in the front country for that matter).

The outdoor school I work for in the summer has had 12 fatalities since it began operations in 1965. Each instructor who works for the schools learns about these deaths in detail. Nothing lives behind the veil. Over the 55 years the school has been in operation there have been hundreds of thousands of students who have successfully completed their courses, and had their lives challenged, stretched, and elevated by the experience. Part of why I wanted to work for the school is that they don’t promise something that ultimately nobody can deliver: risk avoidance, and they do, sincerely, thoughtfully manage the risks that exist in the world.

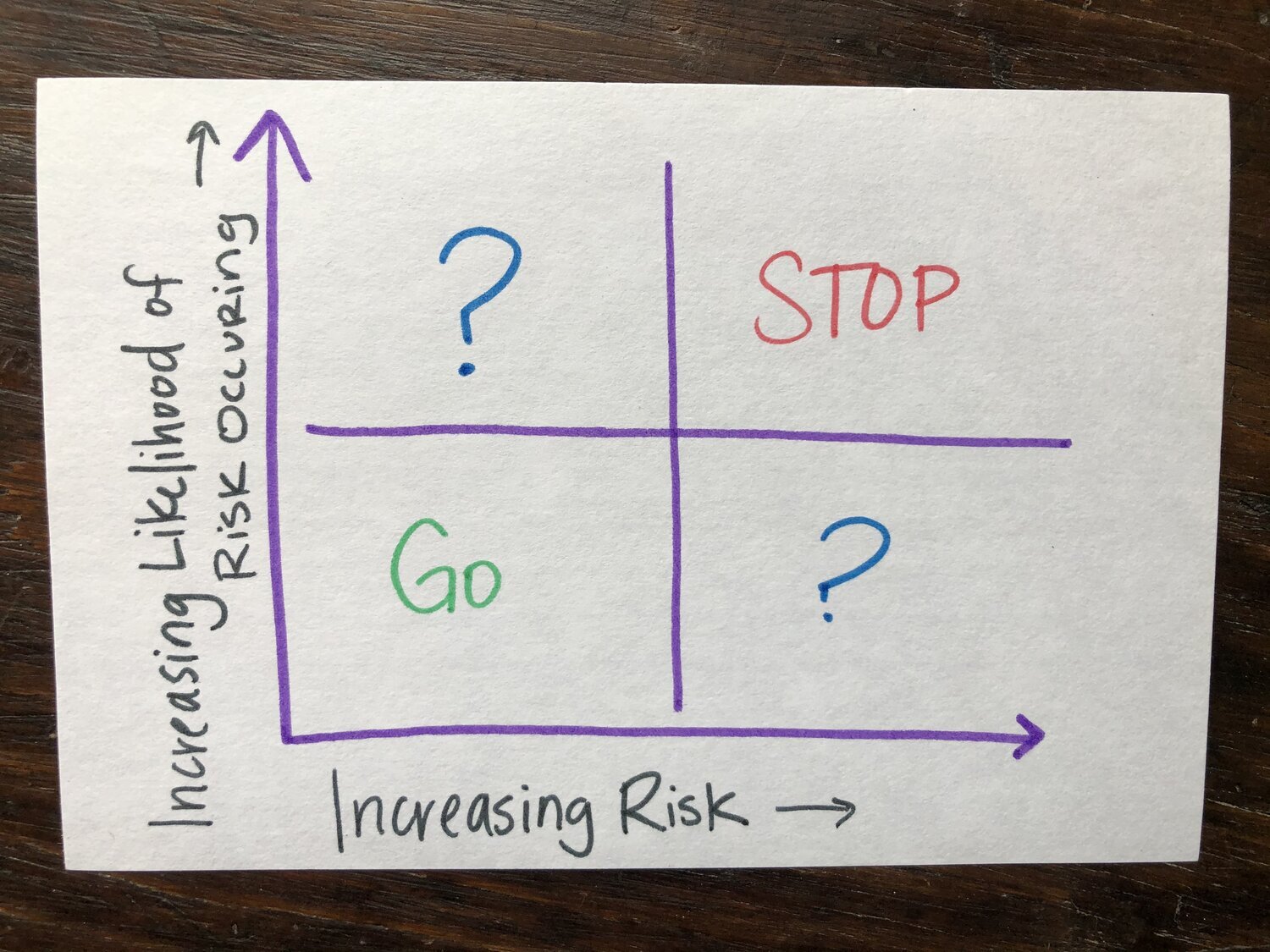

So part of the risk management curriculum is acknowledging that risk is inherent in life. And another part is choosing when and how to take risks. A classic class on risk management looks like this. An instructor draws a diagram (on a white board made out of a plastic bag you slip over trekking poles):

Where this chart meets brass tacks is often in the fight over wet boots. Trying to rock hop on wet river stones with a fifty-pound backpack is a higher risk activity than just sloshing through the river bed with firmer footing. And attempting to take off shoes and cross with tender feet or slippery sandals is a riskier idea too. But this is often a hard sell for teenagers, who are already juggling a lot of new discomforts, who don’t want to add wet boots to the mix. But one of those twelve deaths occurred in a river crossing, and when viewed through this lens, wet socks don’t seem like such a big deal.

Where things get even more complicated in the risk management discussion is when you start talking about individual vs collective risk. In the backcountry one individual putting themselves at risk, really does put the team at risk. Evacuations of a hurt person from the wild put enormous strain on the people executing the evacuation. And what might be a perfectly acceptable activity for one group (say a group trained to read avalanche terrain and utilize avalanche rescue systems) would be wildly inappropriate if one member of that party didn’t have the same expertise.

All of which is to say, rarely do risk management decisions feel neat and tidy and clear. And we are now in a global moment where the narrative of the pandemic has divided risk into two categories: economic and health. Both of which fall into the high likelihood, high consequence square, with diametrically opposed techniques for management. In addition to those categories that are part of the existing narrative, a third major category of risk is emerging: emotional risk.

For those of us who do not have to go out on a daily basis, part of the risk calculus becomes: What is the toll of going out? AND What is the toll of staying in?

It depends—most significantly on what your situation at home is, and on where you go if you choose to go out. None of us get to make decisions in isolation anymore. Maybe we never truly did, but now more than ever, we have to contend with the reality that whatever risks we individually choose to take on, we end up burdening anyone we come into contact with (directly or by ripple effect) with potential consequences.

Decisions that never got a second thought in the past, are now moral dilemmas. New versions of public shaming have emerged. Heartache abounds.

To greater and lesser extents, depending on where you are geographically during this time, we are left to our own devices in choosing how to manage risk. Even living in a city where masks are mandatory and re-opening is happening slowly, I can feel the shift in people’s tolerance for caution as the days stretch on and as temperatures climb.

When a loved one dies, you often recalibrate to remember what is truly important in life. You vow to remember these lessons even when the grief of the loss begins to grow dimmer. But rarely are we able to do this. We acclimatize. We forget. Perhaps we must.

The most exquisite essay I’ve ever read is by Brian Doyle, “Joyas Voladores.” In it he writes:

“So much held in a heart in a lifetime. So much held in a heart in a day, an hour, a moment. We are utterly open with no one in the end—not mother and father, not wife or husband, not lover, not child, not friend. We open windows to each but we live alone in the house of the heart. Perhaps we must. Perhaps we could not bear to be so naked, for fear of a constantly harrowed heart.

Perhaps the only antidote to a harrowed heart is forgetting for a time, before the world reminds us again. Or for the more enlightened, sitting in the perennial distress, day after day with acceptance that this is the human condition.

I don’t know. None of us do. Especially those of us who pretend to know. But there is a security blanket in clinging ferociously to your own risk management calculus and expecting that it is the one that everyone else should be using too. As a people we are generally craving more certainty now that the uncertainty of life is so glaring. And that certainty is just not available, unless we do mental gymnastics and convince ourselves that it is.

Brian Doyle closes his essay in this way:

“When young we think there will come one person who will savor and sustain us always; when we are older we know this is the dream of a child, that all hearts finally are bruised and scarred, scored and torn, repaired by time and will, patched by force of character, yet fragile and rickety forevermore, no matter how ferocious the defense and how many bricks you bring to the wall. You can brick up your heart as stout and tight and hard and cold and impregnable as you possibly can and down it comes in an instant, felled by a woman’s second glance, a child’s apple breath, the shatter of glass in the road, the words I have something to tell you, a cat with a broken spine dragging itself into the forest to die, the brush of your mother’s papery ancient hand in the thicket of your hair, the memory of your father’s voice early in the morning echoing from the kitchen where he is making pancakes for his children.

I could never read another article again, and just re-read this over and over again, and it would contain the bedrock that exists beyond the details of each particular human-narrative. There is love, and there is loss. Love and Loss. Love and Loss. Over and over again.

Therapy in the Time of Coronavirus

With anxiety skyrocketing in the face of immense global uncertainty, therapy, like hand washing, seems advisable for everyone, therapists included.

Coronavirus is, among many other monikers, a leveler. For the first time since becoming a therapist, I’ve had client after client ask me at the start of our sessions, “How are you? How are you in all of this?” The tables turned from the question I consistently ask of them.

I don’t give the full answer, because I reserve that for my hour with my therapist, but the full answer is somewhere close to this: Trying to pin down how I am is like trying to arrest a pin wheel in a tornado. The emotions come on fast and can change in an instant. This has always been true, but it’s occurring at a higher volume now. Some moments I am okay, some moments I am in the spiral of death anxiety. Some moments I am grieving the plans that will not be lived out—visions that won’t come to fruition. Some moments I am fuming at my partner for existing in the same small square footage as me and some moments I am immensely grateful and overcome with love for that same partner. Some moments, I wish I was the dog—pleased with the turn of events. Some moments I am laughing and truly happy. And on and on the wheel spins.

Boundaries are what make therapy work. Confidentiality—the assurance that your therapist will not disclose what you have shared in session—is the bedrock to therapy. Confidentiality is fundamental. But the boundary of how much you as a therapist share of yourself with your client is hazier.

Some schools of thought espouse that the therapist should be the tabula rasa—the blank slate onto which the client can project his/her/their own ideas, needs, beliefs. Other’s believe that there can be utility in thoughtful self-disclosure on the part of the therapist.

You train formally for several years to become a therapist, but in the end the summation of all the training is this: technique will only take you so far—the thing that matters most for therapy being effective is the quality of your relationship with the client. Or said more elegantly by Khalil Gibran: “Work is love made visible.”

I have wrestled often with the question of self-disclosure as I’ve walked down the path of becoming a therapist. One of the therapists I admire most in the world, Tara Brach, a Buddhist psychologist and writer, models self-disclosure as a tool for healing. While I don’t know how much self-disclosure happens in her individual sessions (I’d wager not too much), she has written books where she explores with specificity her own path through depression and grief and anxiety. And this writing has been immensely healing and helpful for so many people—certainly for me, perhaps for her clients too.

The reality of therapy in the time of coronavirus is this: it’s impossible to be a true tabula rasa for a client right now. Everyone knows that everyone (their therapist included) is impacted in some way by the pandemic. And furthermore, therapists are largely conducting sessions by video from their homes. There are dogs barking and cats parading around and babies crying in the background rumble, behind the closed door, or there is quiet—all of which communicates something about the home, and there is the physical space of the home that shows up on the screen. Personal life, especially if you live in close quarters, is revealed.

And is this so bad?

Honestly, I don’t know. None of us do. This is the experiment we are all taking part in, and the results are not in.

The description of healing connection that has always made the most sense to me, is as follows:

“Compassion is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It’s a relationship between equals. Only when we know our own darkness well, can we be present with the darkness of others. Compassion becomes real when we recognize our shared humanity.

— Pema Chödrön

My blog exists in the public domain of the internet. It is a window into who I am as human. It is a window into how I’ve explored my own darkness. And if a client of mine reads this blog, it might be a burden or a gift or both.

On this website, I have encouraged other’s to share their story. In my urging I state: “Shared stories create common bonds that help us to see that we are not alone in our inner sanctums of crazy or divine.” Stories, I’m convinced, are our connective tissue as a species.

We are all living the shared story of coronavirus simultaneously. It is a moment of global human connection that has not existed before in most of our lifetimes. And, how we live out this experience is particular and singular for each of us too.

I don’t go into detail in my sessions with clients when they ask how I am. Because the session time is theirs and it is precious to have a segment of time where you get to explore your particular and singular experience. But there is something that is present in that exchange of “how are you?” A moment where we are two humans acknowledging to each other from screens across town: we are all in this together.

And this is not just true now; this has always been true. No human escapes suffering over the course of a lifetime, irregardless of pandemics. And again, the wise words of the Buddhist nun Pema Chodron rise to the surface: “Compassion is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It’s a relationship between equals.”

And maybe, this moment in time, will shine a light on that truth that will continue unfolding as time stretches onward.

A Birthday Wish

There is an Appalachian birthday song that goes like this:

“When you were born, you cried

And the world rejoiced,

Live your life so,

That when you die,

The world cries, and you rejoice.

Unless you are a child, 34 is not old, but with coronavirus as the backdrop to my 34th birthday, I woke up this morning with thoughts of death. Death is the substrata to the other anxieties that are swirling now. Financial instability, social stagnation, physical inertia are all real and pressing anxieties—but ungirding them all is the ultimate anxiety of death—my own, or someone I love.

I sobbed my way through my 33rd birthday last year. News of my dad leaving my family was three days old a year ago, and his departure, upended my sense of stability in the world and left me reeling for months. The aftershocks still come, and now they are accompanied by this tidal wave of global instability.

I started this blog five years ago today. In my very first blog post I wrote about instability. I wrote about boulder fields in Wyoming—rocks, bigger than cars, that perch one on top of the other, like a set of marbles made for a giant, that can sway under a light human step. A landscape shifting under foot that makes you see with alacrity that stability is an illusion.

It seems that the lesson I am delivered each year on a grander and grander scale is this: the only certainty is change. Changes that creep in over time, like water slowly eroding the river bend into a deeper curve, and changes that happen in an instant, leaving you shattered, standing in the mine field, catching fragments falling all around you.

Over the last five years I have become very attuned to the ways the world can hurt you, and I realize as I head into my 34th year that this attunement has created a deficit in attunement to how the world can save you. Like the beach comber looking for shells, I look out at the horizon with eyes trained to see sharp edges, dark holes, and breadcrumbs that lead to the witch’s den. And there is much to catch the eye.

My question tonight is this: what does it mean to get to the end of your life, and rejoice? A religious faith for some perhaps, but for me, it will be this: that I have loved well. That I have not just trained my eyes for the places and people that hurt, but that I have also trained them for the places and people that heal. That I have noticed, appreciated, and celebrated those connections—no matter how small or large they may be.

Finitude

“My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends-

It gives a lovely light!

— Edna St. Vincent Millay

Here is a hard truth: You cannot have your cake and eat it too. It is a reality most of us want to ignore, myself very much included. But if you pause even for a moment to consider this desire, there is something quite repulsive about it. The greed conjures Veruca Salt in Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory with her whiny, insistent voice shrieking for a golden egg: “I want it, and I want it now, Daddy!”

And yet, many of us, even if we’ve learned to hide our desires better than Veruca Salt, want to be special—want to live outside the laws of the natural world—want very much to have our cake, and eat it too. This is part of the reason why I love Edna St. Vicent Millay’s poem, “My candle burns at both ends; It will not last the night…” which recognizes that we can utilize our finite resources however we so choose, but they are indeed finite. Or said in even more biological terms, in Brian Doyle’s exquisite essay, Joyas Voladoras, “Every creature on earth has approximately two billion heartbeats to spend in a lifetime. You can spend them slowly, like a tortoise and live to be two hundred years old, or you can spend them fast, like a hummingbird, and live to be two years old.”

Our finitude…the finitude of natural resources on our planet…these are things that are so hard to reckon with that most of us choose to ignore the reality. When we see footage of the fires in Australia or hear news of an acquaintances untimely demise, it is easier to bury our heads in the sand than to look at what these truths mean for our own lives.

In 2016, I wrote down the quality I most wanted to inhabit for the year: expansiveness. I wrote in in the style of Ruth Gendler’s Book of Qualities, which brings each quality to life with a persona. This was my description of Expansiveness: “Expansiveness wears fur coats and red lipstick in the winter. She can identify snowflake patterns by taste. On cold nights, she leaves her spare mittens in the woods for the mice, and other small creatures, to find. In summer, she carries a basket full of ripe berries and wildflowers. She always goes barefoot in the rain. One time she walked from the forest to the seashore pressing her ear up against the trunks of tress and then against conch shells. Expansiveness sailed around the world when she was a girl. Now, she does open heart surgery.”

In this paragraph I see, one of my core struggles: I want to be everything. Glamourous one day, an earth child the next; an explorer seeing everything one year, someone who is intensely dedicated to deep understanding of one organ the next. I don’t want to have to choose: I want it all.

Can you have it all, as long as it you don’t demand that you have it all right now? Over the span of a lifetime could you have it all?

While maybe not as frantically grabby and greedy as demanding, “I want it, and I want it NOW,” wanting it all over the course of a lifetime is ill fated too. In choosing breadth of experience, you generally must sacrifice depth of experience. The affirmation of one thing, is a closing of the door on thousands of other things.

It is so much easier to understand hubris in another human than it is to understand hubris in our own particular lives. As I’ve watched my dad, who was always the wisest and kindest person I know, reveal unwise and unkind parts of himself this last year, I’ve found myself reviling from his hubris of believing he could continue to engage in the same way with the family he formed in in the 1980s, and fully engage with the family he secretly formed, and then brought into the light in 2019.

His surprise at the loss—that he couldn’t have it both ways, unmoors me. And then, I remember, I share his affliction. I want all the lives. I, also want to live outside the rules of the natural world. So I am trying to not shrink back from my own hubris. Trying to not do the old routine of sticking my head in the sand, and with my fingers crossed that someday there will be a solution where a person doesn’t have to live with loss—where they just get to have all the goodies. And instead, I am trying to really, really see what I have in my life, and to love it deeply before it is gone. Because our lights are all burning out, and to have wasted the shine searching around one more corner for one more option, instead of seeing what is right here, in the glow of candle right before me, feels like the tragedy of a lifetime.

Wherever You Go…

There are a few book titles that are so brilliant that they can stand alone as wise entities unto themselves. One of them is Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Wherever You Go, There You Are. Because indeed, the one thing we can’t leave behind when we go away from home is our own self. This is not to say that external landscapes don’t have impact on internal landscapes—because they do. But a heavy heart and a worried mind can worm their way into any setting eventually. Or as Thoreau said, in Walden, “the fault-finder will find faults even in paradise.”

External shifts can offer much needed respite or distraction or perspective shifts. All of which can be profound and life altering. But external shifts are rarely the full answer to life’s heartaches. I say this as a person who has tried out the “external fix” route to life’s problems dozens of times, only to find that what I was running from was with me all along. Some people learn not to touch the hot stove after one misplaced hand, others of us, need to get burned a few times before we remember the lesson. I fall into the latter category.

Which is why I take comfort in Portia Nelson’s poem, “Autobiography in Five Short Chapters,”

I.

I walk down the street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I fall in. I am lost. I am helpless. It isn't my fault. It takes forever to find a way out.

II.

I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I still don't see it. I fall in again. I can't believe I am in the same place. It isn't my fault. It still takes a long time to get out.

III.

I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I see it there, I still fall in. It's habit. It's my fault. I know where I am. I get out immediately.

IV.

I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I walk around it.

V.

I walk down a different street

…

I am recently back from spending two weeks leading a backpacking trip in Wyoming. Mountains in general, and the Wind River Range of Wyoming, in particular, are my happy place. Laughter and joy are easier to access when I am out in the mountains. But even my happy place can’t fully guard against my unique array of “deep holes in the sidewalk.” I re-used a journal this summer from a month long backpacking trip I’d led in 2016. And the journal of my 31 year old self was a fairly accurate emotional map for my 33 year old self, which leads me to believe I’m hovering somewhere between chapters two and three of “An Autobiography in Five Short Chapters.”

One of my old familiar deep holes is grasping for contentment “out there” rather than locating contentment in my current reality. The mountains, with their harsh insistence on staying present, on attending to the needs of the moment are the most helpful teachers I have for seeking contentment in what is in front of me, rather than in what eludes my grasp.

And I’m looking at that old familiar “deep hole” in my life with news eyes as I puzzle over the recent choices my dad has made for his life—the wild external shifts he has made as his bid for happiness. And it lends credence to the idea of emotional baggage becoming the unwanted heirlooms that somehow keep passing from generation to generation.

And I hope that someday, I’ll have learned enough to know that I don’t need to keep falling into the same old hole. That instead, I could walk down a different street.

The Fig Tree

I started 2019 out with a Blog Post titled “The Fig In the Hand.” It’s more of a prayer than a post. A prayer that perhaps I’ll be able to savor what is good in my life in the moment rather than dwell in Kierkegaard’s aptly named, “despair of too much possibility.” Or what we call, less elegantly, in modern parlance: FOMO (fear of missing out).

The fig tree quote from Slyvia Plath’s The Bell Jar has taken root in my imagination and become an important metaphor in my life.

“I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn’t quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.

With friends, when I talk about “my figs,” they know I am referring to my ghost lives. The lives I watch from the shore of reality, sometimes with incredible angst or nostalgia, and sometimes with great relief and peace.

A few weeks ago I got a message from a friend who was reading The Bell Jar. It’s been quite a few years since I read the book in full. And so I was surprised and delighted to get a photo of the page that follows the fig tree scene. The next page unfolds like this:

“I don’t know what I ate, but I felt immediately better after the first mouthful. It occurred to me that my vision of the fig tree and all the fat figs that withered and fell to the earth might well have arisen from the profound void of an empty stomach...I felt so fine by the time we came to the yogurt and berry jam that I decided I would let Constantin seduce me.

Along with the quote above, my friend, who is also a student in the despair of too much possibility, wrote, “She could have just been hungry. Something for us to consider.” There is something refreshing about considering the possibility that despair could have a tangible remedy. That yogurt and berries can, on occasion, move a person from existential dread to wanting to a romp with Constantin.

Not all problems have such a simple solution. Slyvia Plath’s life famously ended in suicide. But, it is worth holding onto the possibility that distress can be fleeting. That distress, can sometimes even be fixed.

When my world was thrown into chaos this spring by my dad’s reveal of his hidden life, I heard many things from many people. From one person, I heard: set an alarm to remind yourself to drink water.

The basics: water, food, sleep, are all part of “psychological first aid.” When everything is falling apart, by necessity you need to focus on just surviving. Just remembering to drink water. To eat. To get in bed to try to sleep. And it helps. Not a lot, but a little.

One of my friends works as an Ayurvedic Health coach—bringing the wisdom of an ancient Indian healing system into modern American life. So much of what I’ve learned from her is about attending to the basics in an intentional way.

So I’m adding to my list of possibilities that I maybe should just eat a fig, instead of lusting after metaphorical figs.

I say this knowing full well that I will spend the rest of my life feeling nostalgia for things being “the way they were” with my dad. But “the way they were” is gone. And surviving the void needs solutions great and small.

Nostalgia

Waves of nostalgia

Suffocate me

Like swimming through

An ocean of honey

The memories

Are sweet

At first

But then

So viscous

That I start to choke

Every haunted

Picture frame

holds a ghost

of a life

That was

Of a life

That no longer is

I want to thrash

My way through

This ocean

Back to the time before

Back to the time that was

Back to the time when I knew

Just where to find you

But back has fallen off the map

Now there is just this wave

Of who you were

Crashing over me

Reminding me of

what I had

Of what

I no longer have

Reminding me of

all that is good

And all that is horrible

About being human

In the Shadow of Joy

Despite having a beautiful life, I am intimately acquainted with the Green-Eyed Monster. Jealousy is a pretty odious bedfellow, but for many of us, a well-known, if unfortunate, companion.

I got engaged when I was 27, which for my group of close friends was young. I was engaged to an incredible man I’d dated for most of my twenties, and so when doubt about marrying crept (and then flooded) in, I was confused and dismayed. Calling off our engagement shattered my world and my self-concept. In the aftermath, I constantly berated myself for calling things off, and hoped he would take me back despite the huge damage I’d done.

Slowly, over the course of several years, as the realization dawned that the damage was too deep, and as my own capacity to actually trust the confusing part of me who could not commit to marriage with my first love grew, I opened up to the possibility of falling in love again.

In the meantime, my friends who met their great loves around the time I was exploding my life, started to announce their engagements. The incredible friends who held my broken, sobbing self, together when I imploded were getting married.

These friends I’m talking about are people I love fiercely and without end. I want them to lead the happiest, fullest, most joyful lives. And yet, each of their weddings brought me to tears. And I’m not talking about the tears of joy as they came down the aisle (though those happened too). I’m talking about the less socially acceptable, snot-nosed guttural sobs in the quiet of my bedroom. In part it was an intense jealousy: “they have what I want (and to add insult to injury, what I gave up when it was so close at hand).” And in part it was an intense fear: “their lives are moving on… will there still be room for me?”

It doesn’t feel good to be anything but happy for the people you love when they are in a moment of great happiness in their life. In fact, it feels wretched. But I’ve realized berating myself over my jealousy doesn’t make it go away, and certainly doesn’t make me feel any better.

I spent much of the half decade following my broken engagement single. During my single years, my friends were my everything. My fellow single friends (who wanted to be coupled) held a particularly special place in my life, as they knew with intimacy the way a simple pronoun like “we” could cut straight to the core on a bad day. With each passing year it felt more and more like my coupled friends and I were living on different planets. And in some tangible ways we were. And that is not to say the bonds of friendship disappeared or that we loved each other any less—our friendships remained intact even while the distance between our daily realities grew.

Part of the reason I think support groups are so powerful is that they gather people who have a shared experience, who relate palpably to each other’s unique flavor of sadness. My single friends were my defacto support group. We related with each other in that we’ve each passed through the halls of jealousy around our loved one’s wedding announcements. And we’ve each been slighted by our loved ones for being single in overt and covert ways, that we knew were not intentional, but hurt nonetheless.

There are a million buttons you could push that might cause another person pain. News of a new job shared with someone who is feeling trapped in their current job. A baby announcement to someone struggling with fertility. A description of a vacation or a dinner out to a person who is scraping by financially. A statement of being happy to someone who is in the throws of depression. And on and on. We can never fully anticipate all the ways in which we might push someone’s buttons, and some are impossible to avoid even if you are well aware of your loved one’s sensitive buttons. Some pain is just a reality of life.

So it feels nothing short of a miracle when a close friend who happens to know the constellation of your sore spots, is able to navigate them with kindness, especially when their happiness and your sadness are diametrically opposed. Many of my friends have walked this tightrope with incredible skill and grace, and I am enormously grateful to them for this kindness.

In recent months, my life, has very happily shifted towards partnership, and I feel like I am in the liminal zone between the world where “we” felt a million miles away, and the world where it tumbles, without thought, off my lips.

No matter what happens in the future, I don’t want to forget what it is like to be in a place where I was yearning for something that felt essential to my happiness and yet totally elusive and out of my control. If my life does move in the direction of marriage, I hope that I can say to friends I might invite to a wedding, please know that you don’t have to come if this is financially, logistically, or emotionally fraught for you. Not because they’d necessarily heed this, because we often go out on limbs for people we love, but because it makes such a difference to simply acknowledge that joy can cast a long shadow.

Valentine’s Day, in particular, with its myopic focus on romantic love, is tailor made to cast a long shadow on those single people who want to be coupled. (And of course, not every single person falls into the category of wanting a partner, but many do.) There is absolutely nothing wrong with celebrating romantic love if that kind of love is available to you today, but there is real grace in pausing to acknowledge that romantic love is not a universal commodity and that there are people for whom February 14 is a day to endure, not a day to celebrate. We cannot always be in sync with the people we love. Our seasons of joy and despair will not always align. It seems to me that the hard and essential work, is remembering that joy and despair are two sides of the same coin, no matter which side you find yourself on, in this exact moment. And in this remembering to be kind, to yourself and to others.

The Fig in the Hand

2018 was a year of slowing down and settling in for me. In some ways feeling settled is in fact unsettling for me. A hallmark of my adult life has been movement. Moving homes, moving countries, moving through different mountain ranges. But despite always being on the go, the knowing place in me has always known that there is real value to staying instead of going and to being instead of doing.

But pressing pause on the action is hard for me. As Jonathan Safran Foer captures so well in Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close: “Sometimes I can feel my bones straining under the weight of all the lives I’m not living.”

I’ve always related to Sylvia Plath’s image of the paradox of choice in the Bell Jar: “I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn't quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn't make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.” This is, of course, a wildly privileged lament. One that Kierkegaard, aptly named, “the despair of too much possibility.”

It's not an affliction I’m especially proud of, but it is one that is present for me. A desire to live all the lives. A sadness that reality dictates I have but one life, and nobody knows how long that life will be.

Part of my tendency to do more, be more, and see more is an attempt to subvert this reality of only one life…of limited time. But there is a perversion to this mentality too because so much is missed when you race across the surface and never dive deep where you are.

I know this intimately because for six years I’ve spent a month moving at a slow hiker’s pace through the wilderness. These months in the wild have been my antidote to my tendency to rush. Cell towers haven’t yet penetrated the Wyoming wilderness, and so your whole backpacking world is the world that is directly around you, and nothing more. And the pace of life is slow. And the beauty that exists in an unknown field of wildflowers out there is more exquisite than any art collection I’ve ever seen. And the contentment with life as it is grows naturally.