On Risk

Of all the news articles I’ve consumed over recent months, this one from The New York Times: “How Pandemics End” has, for obvious reasons, grabbed me the most. Because, quarantine fatigue is real, and while not nearly as serious as the pandemic, quarantine fatigue is weighty, as the ambiguous future stretches on and on.

The article identifies two ways pandemics end:

“According to historians, pandemics typically have two types of endings: the medical, which occurs when the incidence and death rates plummet, and the social, when the epidemic of fear about the disease wanes.

I am interested in both of these options: hopeful for the first, and curious about the second. Buddhist mindfulness traditions have long known that the mind bends reality more effectively than any other tool available to humankind. If the medical end to the pandemic does not come, when will the scales collectively tip towards less fear about the disease than the impact of avoiding the disease?

In another lifetime (read: 2019) I was a part-time backpacking instructor. “Risk Management” is a large part of the curriculum you teach students who you are training to be competent in the backcountry. Management is a key term here. In the wilderness, there is no such thing as “Risk Avoidance,” (nor is there in the front country for that matter).

The outdoor school I work for in the summer has had 12 fatalities since it began operations in 1965. Each instructor who works for the schools learns about these deaths in detail. Nothing lives behind the veil. Over the 55 years the school has been in operation there have been hundreds of thousands of students who have successfully completed their courses, and had their lives challenged, stretched, and elevated by the experience. Part of why I wanted to work for the school is that they don’t promise something that ultimately nobody can deliver: risk avoidance, and they do, sincerely, thoughtfully manage the risks that exist in the world.

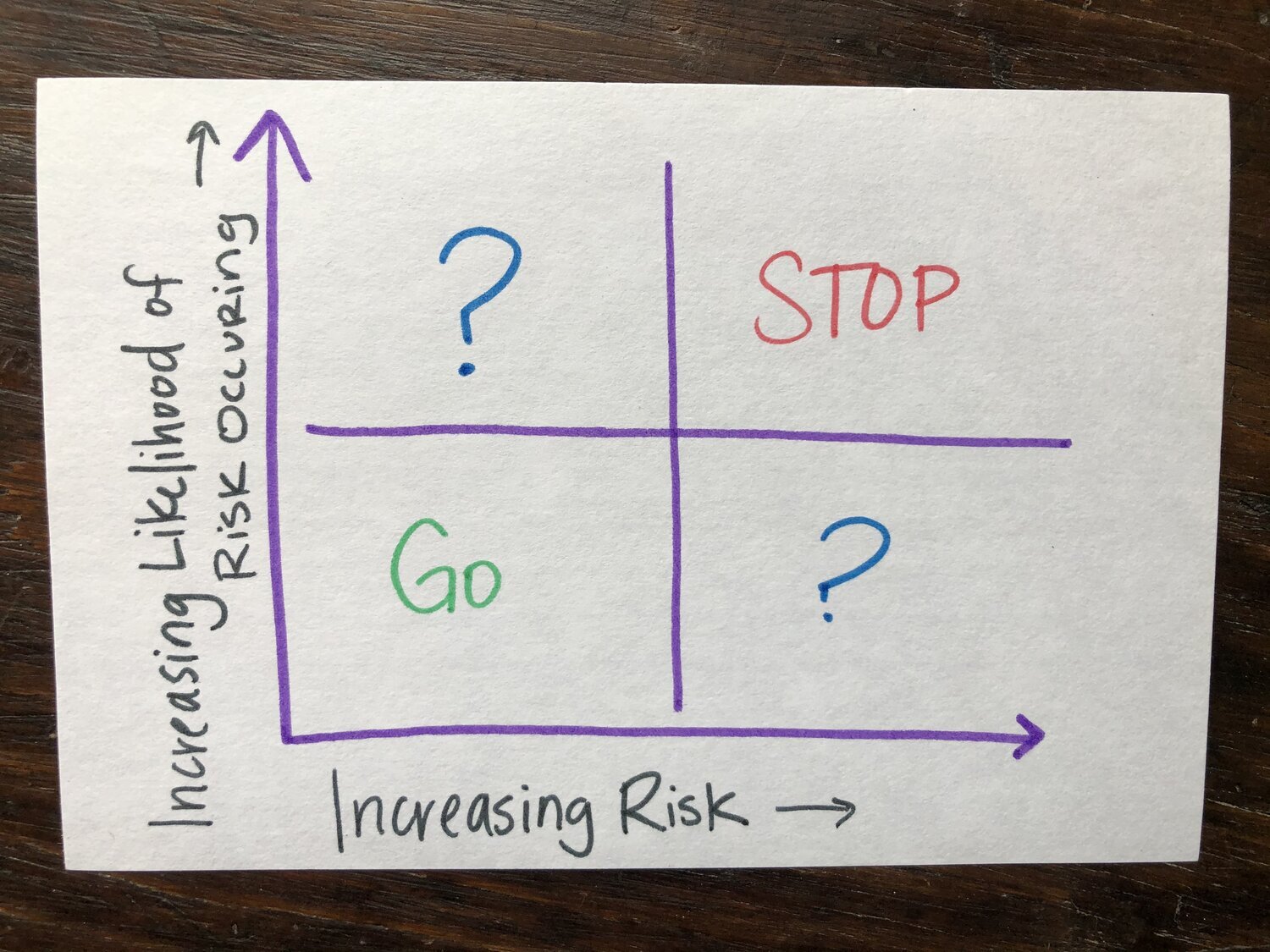

So part of the risk management curriculum is acknowledging that risk is inherent in life. And another part is choosing when and how to take risks. A classic class on risk management looks like this. An instructor draws a diagram (on a white board made out of a plastic bag you slip over trekking poles):

Where this chart meets brass tacks is often in the fight over wet boots. Trying to rock hop on wet river stones with a fifty-pound backpack is a higher risk activity than just sloshing through the river bed with firmer footing. And attempting to take off shoes and cross with tender feet or slippery sandals is a riskier idea too. But this is often a hard sell for teenagers, who are already juggling a lot of new discomforts, who don’t want to add wet boots to the mix. But one of those twelve deaths occurred in a river crossing, and when viewed through this lens, wet socks don’t seem like such a big deal.

Where things get even more complicated in the risk management discussion is when you start talking about individual vs collective risk. In the backcountry one individual putting themselves at risk, really does put the team at risk. Evacuations of a hurt person from the wild put enormous strain on the people executing the evacuation. And what might be a perfectly acceptable activity for one group (say a group trained to read avalanche terrain and utilize avalanche rescue systems) would be wildly inappropriate if one member of that party didn’t have the same expertise.

All of which is to say, rarely do risk management decisions feel neat and tidy and clear. And we are now in a global moment where the narrative of the pandemic has divided risk into two categories: economic and health. Both of which fall into the high likelihood, high consequence square, with diametrically opposed techniques for management. In addition to those categories that are part of the existing narrative, a third major category of risk is emerging: emotional risk.

For those of us who do not have to go out on a daily basis, part of the risk calculus becomes: What is the toll of going out? AND What is the toll of staying in?

It depends—most significantly on what your situation at home is, and on where you go if you choose to go out. None of us get to make decisions in isolation anymore. Maybe we never truly did, but now more than ever, we have to contend with the reality that whatever risks we individually choose to take on, we end up burdening anyone we come into contact with (directly or by ripple effect) with potential consequences.

Decisions that never got a second thought in the past, are now moral dilemmas. New versions of public shaming have emerged. Heartache abounds.

To greater and lesser extents, depending on where you are geographically during this time, we are left to our own devices in choosing how to manage risk. Even living in a city where masks are mandatory and re-opening is happening slowly, I can feel the shift in people’s tolerance for caution as the days stretch on and as temperatures climb.

When a loved one dies, you often recalibrate to remember what is truly important in life. You vow to remember these lessons even when the grief of the loss begins to grow dimmer. But rarely are we able to do this. We acclimatize. We forget. Perhaps we must.

The most exquisite essay I’ve ever read is by Brian Doyle, “Joyas Voladores.” In it he writes:

“So much held in a heart in a lifetime. So much held in a heart in a day, an hour, a moment. We are utterly open with no one in the end—not mother and father, not wife or husband, not lover, not child, not friend. We open windows to each but we live alone in the house of the heart. Perhaps we must. Perhaps we could not bear to be so naked, for fear of a constantly harrowed heart.

Perhaps the only antidote to a harrowed heart is forgetting for a time, before the world reminds us again. Or for the more enlightened, sitting in the perennial distress, day after day with acceptance that this is the human condition.

I don’t know. None of us do. Especially those of us who pretend to know. But there is a security blanket in clinging ferociously to your own risk management calculus and expecting that it is the one that everyone else should be using too. As a people we are generally craving more certainty now that the uncertainty of life is so glaring. And that certainty is just not available, unless we do mental gymnastics and convince ourselves that it is.

Brian Doyle closes his essay in this way:

“When young we think there will come one person who will savor and sustain us always; when we are older we know this is the dream of a child, that all hearts finally are bruised and scarred, scored and torn, repaired by time and will, patched by force of character, yet fragile and rickety forevermore, no matter how ferocious the defense and how many bricks you bring to the wall. You can brick up your heart as stout and tight and hard and cold and impregnable as you possibly can and down it comes in an instant, felled by a woman’s second glance, a child’s apple breath, the shatter of glass in the road, the words I have something to tell you, a cat with a broken spine dragging itself into the forest to die, the brush of your mother’s papery ancient hand in the thicket of your hair, the memory of your father’s voice early in the morning echoing from the kitchen where he is making pancakes for his children.

I could never read another article again, and just re-read this over and over again, and it would contain the bedrock that exists beyond the details of each particular human-narrative. There is love, and there is loss. Love and Loss. Love and Loss. Over and over again.