Mother’s Day

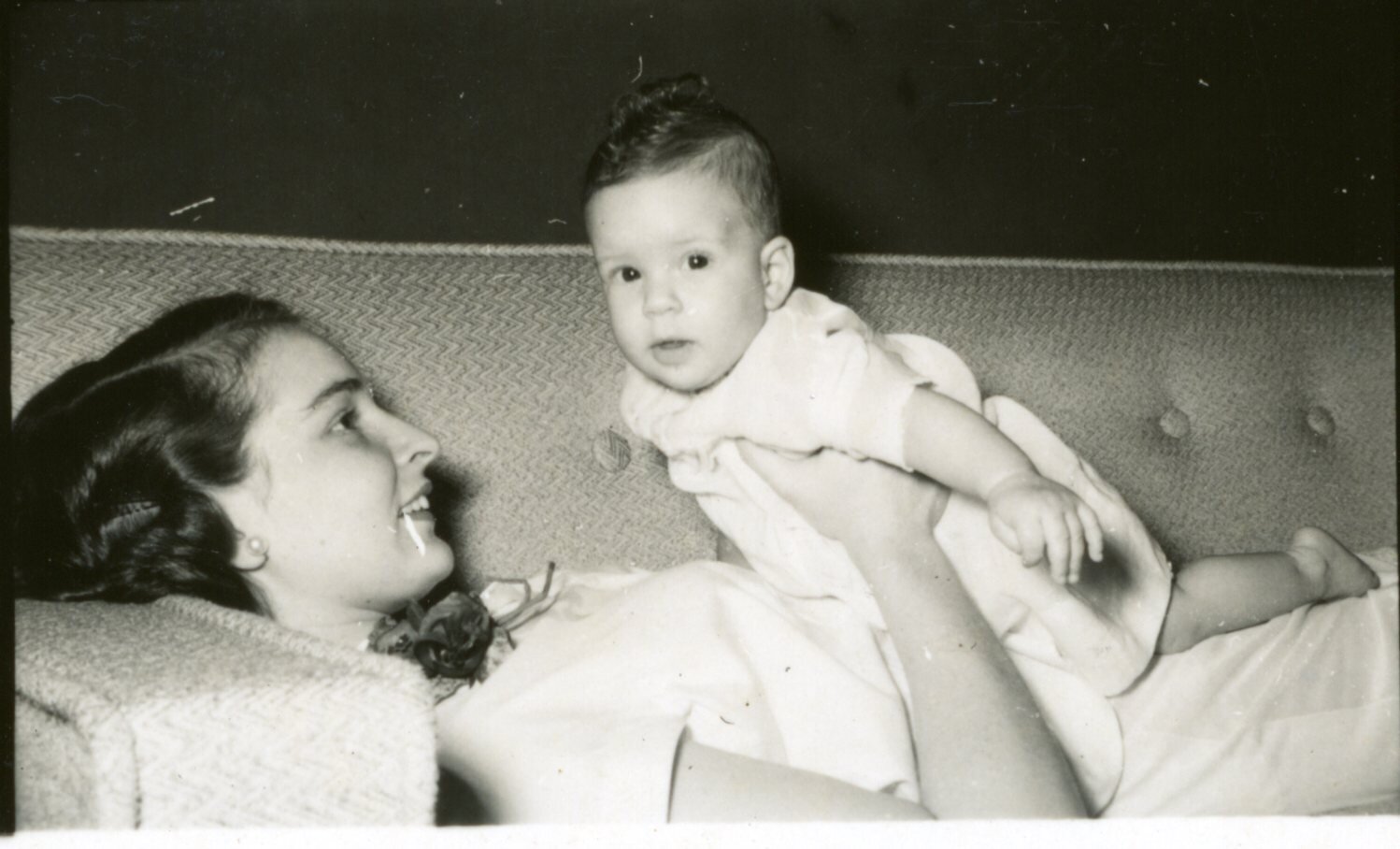

When my parents were young, Mother’s Day was marked by the color rose you wore pinned to your church outfit—a red rose meant your mother was living, white meant she was dead. My mom’s mom died when she was fourteen, and she hated the rose tradition. Not only did she lose her mom, but she also had to wear her private grief publically, pinned on the collar of her dress. I certainly understand her distaste for the antiquated tradition, and also, I wonder at the damage caused by not publically acknowledging that holidays, particularly perhaps Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, are devastatingly hard for many people for myriad reasons.

Charles Dicken’s oft quoted, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” is perhaps the truest description of holidays for most of us. I was thinking yesterday about all the people I know who fall into the white rose category—either symbolically or specifically. Friends whose mothers died before they got to drop them off for their first day of kindergarten or who weren’t in the audience at high school or college graduation or who didn’t get to see them walk down the aisle or who will never meet the first grandchild, or the second. Friends whose mothers cannot be there for the less glamorous, but vitally important, day-in-day-out parts of life. I was also thinking about my friends whose moms are still alive, but who are unavailable because they are either too mentally or physically ill or too scared or too damaged by their own life to be fully present for their child’s life. And I was thinking about my friend’s who want to be moms and who aren’t because pregnancy has been complicated or the right partner hasn’t come along. I was also thinking about the moms, who have given everything to their children, and been snubbed or abandoned by them anyways. Or perhaps the most painful—the moms who have buried their children, at any age, under any circumstance.

And when you start to think about all those people then you realize that right there pulsing beside the wonderful tradition of honoring and showing gratitude for the women who bring us into the world is a throbbing heartache. And that heartache doesn’t get acknowledged in the card shop or by the florists or by the restaurants offering bottomless mimosas alongside your Mother’s Day Brunch. And that oversight—that myopic focus and lack of nuance—is a kind of salt in the wounds.

I celebrated when I turned thirty, delighted to be turning the page after so much turmoil in my twenties. When I turned thirty-one this year, I felt, for the first time, that sense of urgency that if the stars don’t align sooner rather than later, I’ll miss out on being a mom altogether. And so while, I am lucky enough to be the daughter of an incredible woman, with every reason to celebrate Mother’s Day, it’s also become a day tinged with my own particular flavor of sadness. And I don’t need anyone to tell me to have faith or to trust in modern medicine—those aren’t the altars where I worship. I worship at a nexus of reality and hope. And the reality is this: I might not be a mom. And not all pregnancies are joyful. And moms who walk out, might never come back. And dead moms and dead babies are certainly not coming back from the grave.

Not all stories have happy endings. Some do, but they are not the only important and worthwhile ones.

I am not advocating for a return of the rose tradition on Mother’s Day. I don’t think the Hester Prynne model of wearing our shame or our fears or our sadness quite literally on our sleeve is the way forward because not everyone deserves to know our rawest, most vulnerable parts. But I feel certain that ignoring them altogether, and only paying attention to that which is good and happy, is a kind of sickness that we should strive to avoid.